Home > American Imperialism vs. Native Hawaiian Sovereignty

American Imperialism vs. Native Hawaiian Sovereignty

by Open-Publishing - Tuesday 16 August 20051 comment

American Imperialism vs. the Restoration of a Kingdom

by B.Z. Bywydd (GNN) August 11, 2005

Lately I see Native Hawaiian sovereignty compared with Naziism, dismissed as a failed dream, belittled, feared and misrepresented, all by people who seem to have no historical or cultural understanding of Native issues. They speak of "losing the Aloha" and warn Native Hawaiians of this end and that, as if they alone hold the keys to the future.

Most Americans cannot step out of our circle of privilege enough to acknowledge why "affirmative action" may be necessary. We are the "colorblinded" majority who already have doors open to our granted institutions, from the White House on down. It’s what I call a "country club card I refuse to use." Americans also want to force "melting pot" ideals on the world, while glossing over our recent widely racist society, including here in the Pacific. Remember— people of color weren’t allowed in "our" areas, had to stay in a subservient role or possibly be lynched? I mean, that was when I was a little kid— not so long ago!

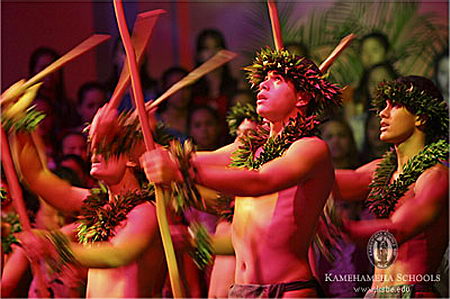

Native Hawaiian interests clash with the American legal system. Critical issues turn to complication for one reason: the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom and subsequent "annexation" by the U.S. left Native Hawaiians without representation. The Kamehameha Schools estate, for example, was founded before the overthrow, for the benefit of children of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Native Hawaiians for the past century have been forced to assimilate into the US economy, legal system, historical record, "melting pot." Many have refused to do so. We now see Americans using any recognition of Native Hawaiian cultural institutions as an excuse to claim "discrimination." It is an abuse of the legal system and a fallacious attempt to erase all vestiges of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

I’m willing to admit that "discrimination" and reverse-racism exists here in Hawai’i— I’m just as much a victim of it as the next "haole boy." Yet I don’t confuse those experiences with cultural preservation and recognition. As far as sovereignty and education go, knowledge and respect generate more of the same.

I challenge all Americans who feel confused about Native Hawaiian entitlements and sovereignty to stop, look and listen. Take a look at the issue from a Native perspective. Ask yourself, what is the remedy for cultural genocide? Imagine going to the "4 corners" of the US to Navajo Nation, and telling all Navajo people they will no longer be recognized as anything other than "American." Tell them that all of their institutions, lands, benefits will now be run by the State and shared with anyone who wants to move there. Oh, and by the way, cowboys will now "help" you elect your tribal officials! How much more "equal" can you be you say?

The problem with the cultural divide in Hawai’i today is the US system has never formally recognized the nationality of Native Hawaiians. Kanaka Maoli have no identity in the American mind outside of "Lilo & Stitch" type portrayals. So whenever sovereignty and entitlement issues come up, the attitude among American pundits is "haven’t they been assimilated yet?" They can’t begin to concieve of a context where Princess Bernice Pauahi was NOT an American and the US flag didn’t fly over Honolulu. We have built a mythology where Hawaii always "belonged" to America, our little grass-shack over the horizon— including all the friendly Natives.

A solution to the confusion regarding Native Hawaiian entitlement and recognition would be to stop referring to Native culture as "race-based." Instead, address all such issues in terms of "cultural recognition," restoration, restitution, and nationality. Ask Native Hawaiians what their future looks like, instead of telling them. Few Americans can truly appreciate the importance of Native culture to Native peoples. For Native Hawaiians, cultural recognition and sovereignty is a matter of survival.

B.Z. Bywydd (GNN)

POB 6271 Hilo, HAWAI’I 96720

http://MetaMagic.org

Complex issues go beyond school admissions and race

By Derrick DePledge

Honolulu Advertiser Capitol Bureau

Maka’ala Rawlins considered himself lucky when he was accepted to Kamehameha Schools as a freshman, although he did not think the school was offering him some kind of affirmative action. He was far from wealthy, but he knew he would be attending a prestigious Native Hawaiian private school that was a clear cut above a public school in quality.

"It’s like another Punahou. Another Iolani. I just thought of it as an opportunity to get a better education," said Rawlins, a college scholarship counselor and community advocate in Hilo, who graduated from Kamehameha in 1997.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals invalidated Kamehameha’s admissions policy Tuesday, ruling that its exclusive preference for Native Hawaiian students is illegal racial discrimination under a federal civil-rights law that guarantees equality in private contracts. The court, in a 2-to-1 ruling, rejected Kamehameha’s argument that its admissions policy was a valid affirmative action plan necessary to reverse the educational and socioeconomic disadvantages of Native Hawaiians.

The ruling was the latest by the federal courts to take a limited view of affirmative action, which, since the civil-rights movement of the 1960s, has been seen as a temporary mechanism to attack historic patterns of racial discrimination and move the nation closer to a colorblind society. But, more subtly, it showed the difficulty of fitting the Native Hawaiian experience into laws that were primarily written to protect and advance the rights of black people and other racial minorities.

Many Hawaiians are troubled by the depiction of Kamehameha Schools as affirmative action and the acknowledgment by the school’s lawyers that the admissions policy is racial. The school, part of a $6 billion trust established by the will of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop, was founded before the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom and many believe should be judged in a political context.

A Native Hawaiian federal recognition bill would give Hawaiians status similar to American Indians and Alaska Natives, with the right to form their own government that could negotiate with the United States and the state of Hawai’i. The bill, now before the U.S. Senate, could give Native Hawaiians a stronger legal claim to defend Kamehameha and other Hawaiian-only programs as political and untangle the obvious conflicts with civil-rights law.

"I think the courts will continue to look very closely at any racial classifications," said Neil Richards, an associate professor of law at Washington University in St. Louis and a former law clerk to Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist.

The Supreme Court’s seminal case on affirmation action came in 1978, when the justices ruled that strict racial quotas at the University of California Davis medical school were unconstitutional. But the court held that race could be used as a factor in college admissions because the state had a compelling interest in promoting diversity.

In 2003, the court upheld an admissions policy at the University of Michigan law school that used race as one of many factors in weighing prospective students. But the court rejected the admissions policy for the university’s undergraduates because race was a decisive factor, virtually guaranteeing that all qualified minority applicants would be accepted over similarly qualified whites. Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who wrote the majority opinion in the law-school decision, found the use of racial classifications so potentially dangerous that they should not be made permanent.

"We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today," wrote O’Connor, who is retiring from the court.

The appeals court in the Kamehameha case - since it was dealing with a private institution - looked for guidance in a 1979 Supreme Court decision that upheld a training program at Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Corp. that reserved half of its slots for black workers. The United Steelworkers of America and Kaiser argued that the preferences would increase the number of black workers in skilled-craft jobs, ending patterns of segregation, while still allowing white workers to advance at the company.

Kamehameha’s admissions policy, the appeals court found by comparison, amounted to an "absolute bar" for non-Hawaiians. "Indeed," the court wrote, "the sub-text to the schools’ policy - that of all those who are found in poverty, homelessness, crime and other socially or economically disadvantaged circumstances, only native Hawaiians count" reinforced race as a determining factor.

Asked last week whether she agrees with Kamehameha that the school’s admissions policy is part of a valid affirmative action plan, Gov. Linda Lingle deflected the question. Although the governor called the appeals court decision "a bad ruling," she said the state would focus on the political relationship between Native Hawaiians and the federal government as it defends legal challenges to the state Office of Hawaiian Affairs and the state Department of Hawaiian Home Lands.

"My position on the admissions policy is that it’s not about race, it’s about a political relationship between the Hawaiian people and the American government," Lingle said. "And the fact is you could go to Kamehameha Schools right now and you could find people who are 95 percent Caucasian and 5 percent Hawaiian and they’re admitted to Kamehameha Schools.

"You could find students who are 95 percent Chinese and 5 percent Hawaiian and they’re admitted to Kamehameha Schools. And it’s true of Filipinos, Japanese and every other ethnic group in the state. In fact, I think the school is a perfect example of the great diversity that we have in our state."

The vivid reaction to the appeals court decision, both in the Hawaiian community and within much of Hawai’i’s political establishment, shows the pride and passion many have for Kamehameha.

Kamehameha’s symbol as a Hawaiian institution has remained strong even though, as the appeals court noted, Pauahi had wanted instruction only in English and by Protestant teachers. It was the original trustees at the school, the court found, who determined that Pauahi intended a Native Hawaiian preference in admissions.

Some Hawaiians are disturbed that civil-rights laws initially intended to protect minorities are being used as a legal weapon against Kamehameha and other Native Hawaiian programs. Native Hawaiians continue to score among the lowest on standardized tests in public schools, and Kamehameha has long held the promise of greater opportunity for students who stand out.

Jon Osorio, the director of the Center for Hawaiian Studies at the University of Hawai’i-Manoa, said he believes there is strong compassion among all people in the state for what Hawaiians have lost since the overthrow. The state’s tourism industry, he said, largely depends on preserving the host culture so people have a practical, as well as an idealistic, stake in not antagonizing Native Hawaiians.

But Osorio also said there are some in the sovereignty movement who object to the way Kamehameha Schools has been portrayed.

"There are a number of people who would argue that affirmative action has absolutely nothing to do with the Hawaiian situation since we are not Americans and the theft of our country does not in any way resemble the kind of situation that African-Americans and people of color face in the United States," Osorio said.

"Their kinds of dispossession have been very different. Ours is a matter of simply taking our government and leaving us really helpless to fight dispossession through law.

"Affirmative action implies that people who have been oppressed over a long period of time should get a helping hand in order to sort of level the playing field. As far as some Hawaiians are concerned and many activists are concerned, it’s not about leveling the playing field, but giving us back our playing field.

"This is our land. This is our government. It was our nation. And so, for those people, Kamehameha’s use of that argument flew in the face of what the sovereignty activists argue."

There are examples, both here and on the Mainland, of schools that promote ethnic identity and cultural awareness but do not restrict admissions based on race. Native Hawaiian-themed charter schools, which are part of the state Department of Education but also receive money from Kamehameha, are reporting some success at reaching Hawaiian children who have not done well at traditional public schools. The federal government, since the 1960s, has taken an active interest in supporting historically black colleges and universities.

Rawlins, the 1997 Kamehameha graduate, said it makes sense for Kamehameha to want to preserve Hawaiian culture and natural for Hawaiian students to want to understand their history. But he said the school should use its wealth to educate low-income children from all backgrounds. The princess had wanted a portion of the trust to be used to educate "orphans, and others in indigent circumstances, giving the preference to Hawaiians of pure or part aboriginal blood."

"I would much rather see them go back to the letter of the will and serve indigents, with a preference to Native Hawaiians," Rawlins said. "Everybody needs a good education.

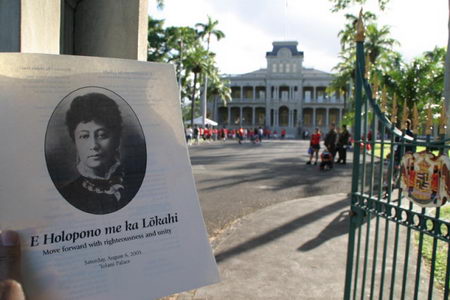

Ke Ali’i Bernice Pauahi Paki Bishop (1831-1884)

Founder of Kamehameha Schools

In 1883, Bernice Pauahi Paki Bishop bequeathed her entire estate for the establishment of a school to educate Hawaiian children. Today, her endowment supports the largest independent pre-kindergarten through grade 12 school in the United States. Born December 19, 1831 in Honolulu, Hawaii to High Chiefs Abner Paki and Laura Konia, Pauahi Paki was the great-granddaughter of Kamehameha I, the warrior chief who united all the islands of Hawaii under his rule in 1810.

Educated by American Protestant missionaries, Pauahi Paki married a young American named Charles Reed Bishop from Glens Falls, New York. He was a widely respected and successful businessman who through banking, real estate, and other investments, became one of the wealthiest men in the kingdom.

When Pauahi Bishop was born in 1831, the native population numbered about 124,000. When she wrote her will in 1883, only 44,000 Hawaiians remained. From childhood, Pauahi witnessed the steady physical and spiritual demise of Native Hawaiians. Captain James Cook’s arrival in Hawaii in 1778 introduced foreign influences that weakened the traditional order of Hawaiian life and culture. Diseases to which Hawaiians had no immunity caused tens of thousands of natives to die in epidemics.

Pauahi's great compassion and enduring generosity still engender devotion to her memory today. She witnessed epidemics of foreign diseases that devastated the Hawaiian population. Her hanai mother, Kuhina Nui Kinau, died of mumps in 1839 when Pauahi was seven years old. During the 1845 influenza epidemic, Pauahi’s teacher, Juliette Cooke, wrote that the young student chiefs, Moses, Alexander, Polly, Elizabeth & J.W. Kinau, “were taken with the influenza & have it very hard. No school now as the schoolroom is devoted to the sick.” All the chiefly scholars eventually recovered. However, Moses, Pauahi’s hanai brother and schoolmate, died in the measles and whooping cough epidemic in 1848 that “made sweeping work among the natives, and probably not less than one in ten will have died before it is over.”

Deeply troubled by the decline, Pauahi Bishop felt a lack of education helped precipitate that decrease. As the heir to most of the lands of high-ranking Kamehameha chiefs, Pauahi “felt responsible and accountable” for having so much. Her husband Charles Reed Bishop said, “Her heart was heavy when she saw the rapid diminution of the Hawaiian people going on decade after decade.” She hoped, he said, “That there would come a turning point, when, through enlightenment, the adoption of regular habits and Christian ways of living, the natives would not only hold their own in numbers, but would increase again like the people of other races.”

In addition, “She wished to establish an institution bearing the name Kamehameha, for which name she had high respect and preference, and a hospital or hospitals and schools for boys and girls were mentioned, and in consideration of the Queen’s Hospital already established...it was decided that schools would be preferred, not for boys and girls of pure or part aboriginal blood exclusively, but that class should have preference.” As a result, she left her estate, about nine percent of the total acreage of the Hawaiian kingdom, to found the Kamehameha Schools.

After Pauahi Bishop’s death on October 16, 1884, Charles Bishop, as president of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Estate’s Board of Trustees, ensured that his wife’s wish was fulfilled. He generously provided his own funds for the construction of facilities and added some of his own properties to her estate. Until his death in 1915, he continued to guide her trustees in directions that reinforced Pauahi Bishop’s vision of a perpetual educational institution that would assist Native Hawaiians to become “good and industrious men and women.”

Pauahi Bishop’s legacy, the Kamehameha Schools, is the sole beneficiary of her trust. In addition to owning 9% of the private property in Hawai`i, the trust has real estate and financial investments nationwide. Revenue generated by these assets has enabled Kamehameha Schools to subsidize a significant portion of the cost of every student’s education, and to provide supplemental financial aid to students who cannot afford the nominal tuition and fees charged. It is the philosophy of KS that no student be denied admission or continued attendance at KS because of inability to pay school fees. Kamehameha’s policyon admissions is to give preference to applicants of Hawaiian ancestry to the extent permitted by law.

Today, Kamehameha Schools encompasses three K-12 campuses enrolling 5,100 students. It also operates 32 preschools serving about 1,400 children statewide and offers more than $15 million in college financial aid to Native Hawaiians annually. Since its founding, Kamehameha has graduated more than 20,500 young Hawaiian men and women. Currently, all graduates apply and are accepted to colleges nationwide. Of the 93-97% of graduates that actually enroll in post-high school programs the fall after their senior year, about an average of 80% attend four-year colleges and 15% attend two-year colleges.

Forum posts

16 August 2005, 08:05

As long as the military wants to use Hawaii as their own resource for stockpiling weapons and playing war and occupying the aina for their warmongering, Hawaii will never again belong to the Hawaiians.